Instagram changed contemporary painting

What started as a great idea, ended up being a monumental trap

I got my Substack profile six months ago, and it has helped me to meet new people, read stupendous and well researched texts, and have great debates about art. It also has helped me to pinpoint elements that were making me uncomfortable about Instagram and the experience of it, by comparing the two apps.

I got my Instagram profile in 2016, almost a decade ago, and we seem to have forgotten how things were in the arts pre-insta. So this is just a reminder, also for myself, of what happened with our images in the last decade, with a special focus on painting.

Immediacy

The first thing I noticed when I opened my Instagram was that all information has the same visual value. With its layout, every post is the same size and format. Back then I already wondered about the negative implications of visually organizing the information like that: A work of art, a party, a killed Palestine kid, a cheeseburger… All of these pieces of information have the same value and, in a perverse twist, almost the same meaning. They meet in the muddy middle. This makes us frivolize important information but also elevates frivolous information into something falsely important. For the artists, this has messed us up. Art needs to be thoughtful but to make it so takes time. What happens when we prioritize immediacy? Critical thinking is worthless, cause it takes more time to generate than empty information, but doesn’t give anything extra back to the creator. The result is a huge discredit of conceptual depth in painting and a lack of commitment to the idea of painting as a transformative tool. Paintings that work best are decorative, easily understood and as such, forgettable. We are creating undemanding paintings.

Immediacy is the term of the decade. A big effect from it is, painters are repeating themselves constantly. The value of their work is suddenly measured by the amount of milliseconds of scroll-down a viewer invests in it. This means your style has to be immediately recognizable as yours. For me, this is the exact difference between having a style and having a language: some artists, by repeating the same aesthetic decisions over and over, develop that easily recognizable spark. Some other artists develop their unique calligraphy by exploring different subjects, techniques and concepts. Not to mention the complete oblivion of the idea of evolution in a painter’s language. Some decades ago, critics would talk about evolution as a positive factor in a painters’ career. I know the term can be muddy waters too, but some minimal variation, wander around, at least a mild devenir of the artist with their work… We are talking about young artists, where are their crazy experiments? If we have to prioritize the fast pace of recognition over non-identifiable experimentation, repetition seems a more productive way to go. Therefore, many painters always paint the same subject matters, with the same color palettes, the same techniques, the same canvas sizes and formats and the same decisions they made a decade ago. Their paintings are too similar to each other. This is traditionally called mannerism.

Content Vs. Art

In the last few years of Instagram we all have noticed the shift into content over cultural artefacts. There is no need to explain the difference between content and culture, everyone has noticed it by now. Culture makes your brain roll, content makes your brain rot.

Instagram in principle was created precisely for fixed image artists, but now it’s taken up by many artists who are simply showing crafty techniques on reels. Artists of the random splatter have proliferated like mushrooms. These are not the artists with interesting insights about the state of the world, who later will be part of the best museums and cultural institutions. These artists are obsessed with the technical aspects of their craft, but leave us an empty soul regarding interesting ideas. Artists filmed sped up filling up canvases in a very flashy and gestural manner, detail shots of acrylic paint dripping on a canvas, smiley people turning around their canvases for self-aggrandising great reveals… This is the art that is most popular on Instagram now. Many times the pieces don’t even matter, they are called Untitled and they make us all wonder that, if that is art, then the horrid affirmation my kid could do that turns to be true. The other day, I stumbled upon this Instagram account and it made me laugh so much, at least the holder is honest.

The size affects the size

One main illusion from our phones is the fact that they are a window to a reality, even if that reality is digital. It might be true, but it implies a very tiny window to look through. This is not exclusive from Instagram, but for any appreciation of art on a phone. No viewer can argue that the experience of looking at a painting in the screen of a phone is even remotely comparable to having the canvas in front of your eyes. We can’t even replicate it in a website on a big computer screen. Now, imagine to enclose a 2 meters tall painting into a rectangle of 7x5 cm. You are going to miss 90% of the real surface’s information. This fact has lead painters to adapt their ideas to an image that can work well both in 200x100 cm, and in 7x5 cm. Bigger shapes, simpler compositions, fewer elements on the surface, chromatic shortening, minimalism over baroque, and a particular flatness on the surface that can easily make the cut for tiny window appreciation.

For example, take these two paintings:

The first painting is 193 cm tall. The second one, 180 cm. Even though their sizes are similar, the experience of Cecily’s painting on a phone screen is much worse than Guston’s. Something in the way Guston painted simply goes better with the tiny window effect. Cecily’s painting gets flatter, you may have the intuition that in real life it’s richer in texture and detail, but you definitely won’t appreciate it. This doesn’t mean that Guston painted like this because the tiny window told him so. But it might mean many contemporary painters get more praise for images like the second one, than for ways of doing like the first. And this might affect aesthetic conclusions in their art practices or the way they understand contemporary painting.

On the other hand, it’s a very common practice for any painter to take a photo of the canvas you are working on and look at it tiny on purpose. This helps organizing composition in general terms, and see where the general color scale is leading you to. It’s the contemporary version of walking away from the canvas. Painters now usually have less space to walk distant than before. It used to be possible when space in cities was not scarce, so artists would have big ateliers and many square meters to work and move freely. Now we have tiny studios and look through tiny windows.

And talking about tiny… Look at what Instagram did to galleries and cultural institutions:

Thank you CCA Andratx, for giving such remarkable visibility to great works of art… Isn’t this picture absolutely ridiculous? How did we grow so accustomed to this shit? These pieces of art that took many hours to create are shown in a 4mm rectangle, with a big white space in the middle… What is this?

Likes and followers: a love and hate relationship

In this shameful moment I admit my ego wants what it wants. Likes are that element we all know is bullshit, though we all check incessantly. The like was a revolutionary invention, with the capacity of spreading brief love, in the brief shape of a brief heart. But it turns out, the like is not free of politics. We may press like because we truly like something. But we also deal with likes as if it was hard drugs; I fix you, you fix me. Sometimes we like something out of pity for the person who posted it. Or we like it falsely, to keep the status quo of a friendship. Or to make ourselves excel from other people in front of a potential client. Sometimes we even like tragedies, only to say “I saw this, I hear you”. So it’s not that simple as a liking gesture, and it’s not devoid of ethics.

The like has changed our perception of beauty. In Spanish we have two words for beauty: bonito and bello. Bonito means pretty, it’s as helpful as pretty: it can get you out of an uncomfortable situation (–What do you think about my art?) but it has the same empty meaning. Bello means beautiful, but almost in a sense of sublime. Nobody uses bello anymore. Bello seems reserved for a Botticelli painting, but nobody goes to a contemporary painting show and says qué bello! The truth is, no contemporary work of art seems to have enough weight to be called bello. These two categories, beautiful vs. pretty, are more entangled than ever, and I believe it’s because the effect of likes on social media. The like is in principle to say how pretty. The problem is this paradox: nothing looks ugly and pretty, but many things are ugly but beautiful. One day I’ll write a whole dissertation about the relationship between prettiness and beauty, but today I can’t digress. I will just say, I like it has stoped debates about the value and weight of an artwork as if it was the ultimate valid argument. But we all know it’s a capricious territory, unquestionable, subjective and kind of empty.

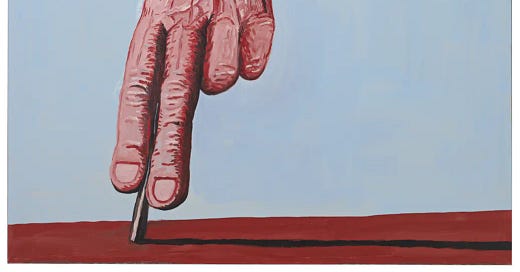

There are thousands of examples of ugly beautiful things, I show you one here so you know what I mean:

This work of art now has the value of History backing it up. However, it would have been censored on Instagram, if done nowadays.

Ads ads ads…Ads everywhere!

Well, what to say about this matter… I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe… Once I got an ad offering fake Spanish national IDs, and I’m just surprised they could compete with clothes brands to make an entrance to my wall, a hurray for the marketing skills of that con man.

Many years ago, I tried myself to pay ads on Instagram to spread out my paintings. I was young and innocent, and I believed the daisyparrises and christinaquarleses of the world did it to gain traction to their profiles. Little did I know, even though some artists surfed the uphill of popularity admirably well, the art world kept functioning mainly outside the internet, and these artists, surprise surprise, live where you should live, work with who you should work with, and sell their paintings to whom you should sell them. I did my first ad and received a message from a real friend telling me he was getting my ads even though he was already a follower. I spent money on showing my work to people who was gonna see my work anyways in person and for free. I tried once again years later, and the painting I wanted to promote got censored. Instagram informed me that, due to the nature of the image I was not allowed to pay to the platform to spread it around. This was the picture:

That was the end of my ads experiments. It simply does not work. I never gain new followers, neither new sales, neither a new gallery. I just got more bulky likes. I gave Instagram extra money, apart from the money I already give by just accepting their terms and conditions.

The lack of text, the lack of dialogue

This is the part I am most concerned of. Reading on Instagram is beyond uncomfortable. The font size is too tiny, The space for comments too tight and the vibe is too emoji-ish. Some people post screenshots of texts and I’ve read entire articles only accessible with a microscope just zooming and holding with two fingers laughably separated, only because I could not be bother enough to follow the link to a website. Sometimes there is no link at all, so even if I wanted to read it properly, I would need to do the extra work of searching it in Chrome. Life is too short. The amount of brilliant texts I must have missed is incommensurable. Since I just didn’t know about Substack until recently, I wondered for a decade where the intellectuals were. I wondered if we had just become dull as a collective. The world of images without ideas… Is that what painters and photographers always wanted? Well, now take it, eat it. We ate it, we ate it all and now we are fed up. Visuals without concept. Form without meaning. Aesthetics without ethics… it’s all very strange. At the same time, it has been a decade of art writing crisis. Art critics have almost disappeared, and the silent layout of Instagram had probably something to do with this sudden extinction, along with the fall of press in general and the confusion between fact, opinion and offense. However, I find funnily ironic that, entangled in the problematics of information in the digital era, most of the art writers and curators chose this particular moment to write the most opaque, cryptic and impossible to follow, full of intellectual jargon art texts. Hahaha, well done, art writers, you attracted zero people, nobody understood shit, and you got no praise for it whatsoever. Congratulations on your hard work.

In my decade of Instagram I’ve never had a debate about art or something that could remotely resemble one. Nor I felt I had enough space to express myself regarding my paintings. I was recently reminded by a friend that not all artists are good at explaining their ideas in written or spoken form, in that case Instagram can be a great tool for them. However, I believe the world of ideas and the art world are braided by their very nature. As spectators, we all had to face the fact of meaning in a work of art; what moved an artist to do it, why the artist arrived to this or that conclusion… As artists, we all have faced the moment of choosing what to talk about with your art. And believe me it’s important, cause if you don’t choose, you do no painting. The fact that sometimes art can leave you speechless doesn’t mean it’s devoid of any meaning. Art is a collection of momentary choices, conscious or unconscious, that can be tracked down when talking about the art work. It’s interesting to ask a painter why did they paint that, why did they choose those colors or that subject matter. If the answer is because I felt like it, that’s an honest answer and respectable too. But maybe you get surprised to know how thoughtful and consistent the artist’s methods are. Or maybe you just confirm they have an empty brain, and it corroborates why their art didn’t talk to you in the first place. In The Observer Effect, Barry Schwabsky has a thesis I agree with: at the beginning of Avantgarde, abstraction was erected as a sort of god of the arts, above any other manifestation. All abstract painters would defend abstraction as the only valid and purest way to paint. Only to realize with time, that all painting is an abstraction. Something similar happened with conceptual art; it was created and defended as the only way to go for innovation, only to realize that all art is somehow conceptual, even painting. All paintings are enclosed in a space between meaning and abstraction. And this relationship has been sadly wiped out of many works of art inside the realm of Instagram.

To finish this essay, I will admit I don’t dare to erase my Instagram account. I’ve fallen into the perils of the sunk-cost fallacy. But I’ll also admit that it makes me feel awful. I want to mark 2025 as the year when I stopped surfing it. I’ve read it’s not a good idea to erase the account fully either. Apparently, somebody can grab your name –in my case, my real name– and use it to sell shit to people who believe they are talking with you. The best idea is to leave it as a portfolio excerpt and abandon its rotting use. Now my endeavour is to drag all the people I collected there over the years to my newsletter. For that, please subscribe!

Hey Tamsin!! I am very happy this resonated with you :) I totally get what you mean about art and ideas, it seems there is a lot of confusion on this field in the art world. I always thought that artists who choose conceptual art as their medium are artists who simply don't have the craft or skills, hahaha. Obviously it's not true, but I just wonder why anybody with the skill would chose to wipe it out of their lives and practices, if it's the most beautiful part of the arts to practice it. At the same time, it seems there has been a bit of gatekeeping in relation to ideas from conceptual artists: the fact that you prioritize ideas over perceptible material elements doesn't mean that the artists who prioritize perceptible material elements over ideas in their work don't have any idea behind. A landscape is also an idea. A copy from reality can be also an idea, and a pure abstraction can have an idea behind too! I just hope you never give up to the world of ideas, either to the perceptible material art :) Cheers!

Excellent essay, thank you Marina.

We too struggle big time with two of the points you raise in your text: immediacy and content. Too much of the first and too little of the latter.

Those notions however seem to be baked into the current (contemporary) art ecosystem. Galleries want shows of new artists to sell out immediately and push the prices up towards more profitable levels. Generally, that implies work that is less 'difficult', images that are understood at first sight, at the expense of what you call 'art' and 'beauty'. Many artists are happy to comply. Last year, a gallery here in Brussels sold out the first ever show of a 28-year old artist on opening night. The cheapest price for a painting was 35k€. About 3 works in the show were indeed spectacular. Most of them were just average.

You mention the difficulties of representing art on Instagram.

We're struggling with another IG trend that you haven't mentioned: Instagramable shows and the enshittification of exhibitions. Kusama is an amazing artist (especially early in her career) but I have developed a polka dot and infinity room allergy. James Ensor is not my favourite artist, but he's an exceptional post-impressionist painter. The show in Antwerp was so much about 'experiencing' the visit that you lost sight of the art. The result: 450k visitors...

To end on a positive note, I see a lot more focus—both from collectors and leading galleries—on older artists and the estates of deceased artists. I have a feeling that collectors are seeing the brevity and financial risk of 'Instagram art' as well.